Seqirus, a global leader in influenza prevention, today presented new scientific data at the Options for the Control of Influenza (OPTIONS X) Conference in Singapore that demonstrated circulating influenza B/Victoria (B/Vic) viruses are a closer match to cell-based B/Vic vaccine viruses compared with egg-based B/Vic vaccine viruses.1 The data builds on a previous analysis that evaluated the level of match between circulating influenza A (H3N2) viruses and corresponding H3N2 cell and egg-based vaccine viruses, highlighting the potential role of egg-adaptation in varying vaccine effectiveness.2

The cell-based B/Vic study results are reported from a retrospective analysis that evaluated the degree of match between circulating influenza viruses and candidate vaccine viruses (CVVs) derived from both egg and mammalian cells (Madin-Darby Canine Kidney MDCK) over multiple influenza seasons.1

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), growing influenza viruses in eggs can introduce changes in the vaccine strain that may result in the body’s immune system producing antibodies that are less closely matched to the circulating influenza viruses.3,4 Cell grown CVVs avoid egg-adapted changes and may result in vaccine virus strains that are more closely matched to the circulating influenza virus strains.3

The data collected from both A (H3N2) and influenza B strain analyses provide continued support for the use of CVVs derived from cells in the influenza vaccine manufacturing process. For the 2019/20 influenza season, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended four cell-based CVVs along with four-egg based CVVs Influenza A (A(H1N1)pdm09, A(H3N2)) and Influenza B (B/Yamagata and B/Victoria).5

“This study provides ongoing validation of cell-based influenza vaccine technology that can offer a truer match to the WHO vaccine selected strains for each influenza season,” said Russell Basser, MD, Chief Scientist and Senior Vice President of Research and Development at Seqirus. “Egg-based vaccines continue to play a critical role in the fight against influenza, but it’s also important to evolve approaches to avoid variance introduced during the egg-based influenza vaccine manufacturing process.”

Seqirus is the largest U.S. cell-based influenza vaccine manufacturer.6 The Seqirus manufacturing network includes a state-of-the-art facility in Holly Springs, North Carolina that utilizes cell-based technology and was built in partnership with the U.S. Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) to support pandemic preparedness.7

“The global burden and impact of influenza remains an important public health concern, and it is imperative to continue researching and developing innovative influenza vaccines,” said Anjana Narain, Executive Vice President at Seqirus. “The findings presented at OPTIONS X reinforce the role of innovative technologies, such as cell-based vaccines, to help protect people and communities from seasonal influenza.”

About the Study

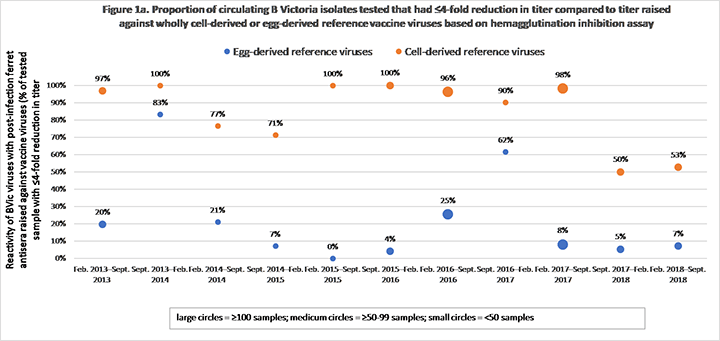

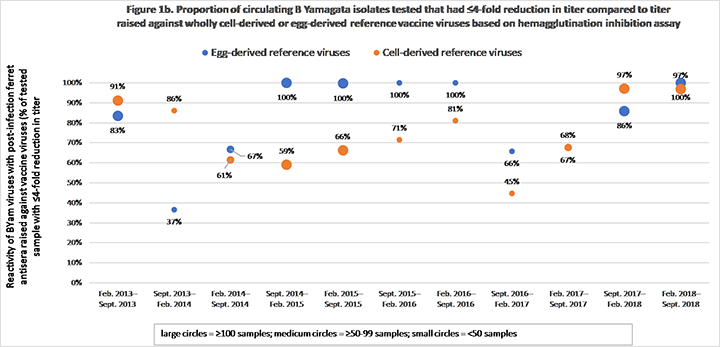

Using publicly available reports from the Worldwide Influenza Centre, London (Crick) for the Northern Hemispheres for influenza seasons 2013-2018, Seqirus evaluated the degree of match (antigenic similarity) between circulating B/Victoria (BVic) and B/Yamagata (BYam) virus isolates and the reference (candidate vaccine virus) virus derived from both eggs and Madin-Darby Canine Kidney [MDCK] cells over 5 influenza seasons. Results found there was a higher proportion of similarity between the circulating BVic influenza virus and the cell-based reference virus compared with the egg-based reference virus (Figure 1). This finding was not identified in the BYam virus (Figure 2). The data supports a previous descriptive analysis of A (H3N2) strains that showed circulating A (H3N2) viruses were more antigentically similar to the A (H3N2) cell-based virus compared with A (H3N2) egg-based virus. Furthermore, there was little or no similarity for more than half of the influenza seasons evaluated between the circulating A (H3N2) virus and the egg-based A (H3N2) virus.1,2,8

Figure 1a

Figure 1b

About Influenza A (H3N2)

Influenza A, which can spread from animals to humans, is the most common form of influenza. The influenza A strains most frequently found in people are H1N1 and H3N2.9 Influenza seasons that are dominated by A (H3N2) tend to be more severe, particularly among high-risk groups such as older adults and younger children.10 While all influenza viruses undergo mutation from year to year, A (H3N2) strains are prone to mutations that result in mismatch to the A (H3N2) strains in influenza vaccines. During the vaccine manufacturing process, A (H3N2) viruses have been shown to adapt to growth in eggs, which can potentially reduce vaccine effectiveness.11

About Influenza B

Influenza B can only spread from human to human. The influenza B viruses that currently circulate during most influenza seasons include: B/Yamagata (BYam) and B/Victoria (BVic). Influenza B can cause seasonal outbreaks that occur throughout the year, but it is not known to cause pandemics.8,12

About Seasonal Influenza

Influenza is a common, highly contagious infectious disease that can cause severe illness and life-threatening complications in many people.13 To reduce the risk of more serious outcomes, such as hospitalization and death, resulting from influenza, the CDC encourages annual vaccination for all individuals aged 6 months and older.14 Because transmission to others may occur one day before symptoms develop and up to 5 to 7 days after becoming sick, the disease can be easily transmitted to others. Influenza can lead to clinical symptoms varying from mild to moderate respiratory illness to severe complications, hospitalization and in some cases death.12 The CDC estimates that 959,000 people in the United States were hospitalized due to influenza-related complications during the 2017-2018 influenza season.15 Since it takes about 2 weeks after vaccination for antibodies to develop in the body that protect against influenza virus infection, it is best that people get vaccinated to help protect them before influenza begins spreading in their community.13

About Seqirus

Seqirus is part of CSL Limited (ASX:CSL), headquartered in Melbourne, Australia, and was established on 31 July 2015 following CSL’s acquisition of the Novartis influenza vaccines business. As one of the largest influenza vaccine providers in the world, Seqirus is a major contributor to the prevention of influenza globally and a transcontinental partner in pandemic preparedness. Seqirus operates state-of-the-art production facilities in the U.S., the UK and Australia, and manufactures influenza vaccines using both egg-based and cell-based technologies. It has leading R&D capabilities, a broad portfolio of differentiated products and a commercial presence in more than 20 countries.

About CSL

CSL (ASX:CSL) is a leading global biotechnology company with a dynamic portfolio of life-saving medicines, including those that treat haemophilia and immune deficiencies, as well as vaccines to prevent influenza. Since our start in 1916, we have been driven by our promise to save lives using the latest technologies. Today, CSL — including our two businesses, CSL Behring and Seqirus — provides life-saving products to more than 60 countries and employs more than 22,000 people. Our unique combination of commercial strength, R&D focus and operational excellence enables us to identify, develop and deliver innovations so our patients can live life to the fullest. For more information about CSL Limited, visit www.csl.com.

Intended Audience

This press release is issued from Seqirus USA Inc. in Summit New Jersey, USA and is intended to provide information about our global business. Please be aware that information relating to the approval status and labels of approved Seqirus products may vary from country to country. Please consult your local regulatory authority on the approval status of Seqirus products.

Forward-Looking Statements

This press release may contain forward-looking statements, including statements regarding future results, performance or achievements. These statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors which may cause our actual results, performance or achievements to be materially different from any future results, performances or achievements expressed or implied by the forward-looking statements. These statements reflect our current views with respect to future events and are based on assumptions and subject to risks and uncertainties. Given these uncertainties, you should not place undue reliance on these forward-looking statements.

US/CORP/0819/0162

###

MEDIA CONTACT

Polina Miklush

+1 (908) 608-7170

Polina.Miklush@Seqirus.com

REFERENCES

- Rajaram S., P. Suphaphiphat, M. Haag, et al. (2019). Retrospective evaluation of antigenic similarity between egg-derived Versus cell-derived influenza vaccine reference strains and circulating influenza B-Victoria and Yamagata viruses. Presented at OPTIONS X, August 2019.

- Rajaram S., Van Boxmeer J., Leav B., et al. (2018). Retrospective evaluation of mismatch from egg-based isolation of influenza strains compared to cell-based isolation and the possible implications for vaccine effectiveness. Presented at IDWeek 2018, October 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC). (2019). Cell-Based Flu Vaccines. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/cell-based.htm. Accessed August 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC). (2018). Selecting Viruses for the Seasonal Influenza Vaccine. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/vaccine-selection.htm. Accessed August 2019.

- WHO. (2019). Candidate vaccine viruses and potency testing reagents for development and production of vaccines for use in the northern hemisphere 2019-2020 influenza season. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/influenza/vaccines/virus/candidates_reagents/2019_20_north/en/ Accessed August 2019.

- Data on file. (2019). Seqirus USA Inc.

- Data on file. (2019). Seqirus USA Inc.

- The Francis Crick Institute. (2018). Worldwide Influenza Centre: Annual and Interim Reports – February 2018 interim report. Retrieved from https://www.crick.ac.uk/research/worldwide-influenza-centre/annual-and-interim-reports/ Accessed July 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (2017). Types of Influenza Viruses. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/viruses/types.htm. Accessed August 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (2017). Seasonal Influenza A(H3N2) Activity and Antiviral Treatment of Patients with Influenza. Retrieved from: https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/han00409.asp. Accessed August 2019.

- Wu N.C., Zost S.J., Thompson A.J., et al. (2017). A structural explanation for the low effectiveness of the seasonal influenza H3N2 vaccine. PLOS Pathogens, 13(10): e1006682. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1006682.

- Healthline. Influenza B Symptoms. Retrieved from: https://www.healthline.com/health/influenza-b-symptoms. Accessed August 2019.

- CDC (2018). Key Facts About Influeza (Flu). Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/keyfacts.htm. Accessed August 2019.

- CDC (2018) Key Facts About Seasonal Flu Vaccine. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/keyfacts.htm. Accessed August 2019.

- CDC (2018). Estimated Influenza Illnesses, Medical Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths in the United States – 2017 – 2018 Influenza Season. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/2017-2018.htm. Accessed August 2019.